[HO CHI MINH CITY] High-speed rail is generating buzz in Vietnam, as plans are being drawn up to start building two lines connecting the capital Hanoi to China before 2030.

The initiative promises substantial economic benefits for the South-east Asian country, but could also heighten its economic dependence on China, said Dr Majo George, a senior lecturer at The Business School of RMIT University in Vietnam.

The upsides of the two rail routes are clear, he said, because faster access to Chinese markets and ports will open up new business opportunities and lower logistics and operations costs.

“High-speed rail will be a game-changer for cross-border trade between Vietnam and China,” he said, adding that this was particularly crucial for the country’s agricultural sector, which stands to benefit from such expedited access.

Rail connectivity will also enhance Vietnam’s trade with Central Asia and Europe, through China, and serve as a vital gateway for trade flows between the Asean bloc and China.

“The high-speed rail links between Vietnam and China could open the door for greater rail infrastructure cooperation opportunities among Asean countries, to expand the cross-border rail traffic network,” a spokesperson of logistics firm ITL Corporation told The Business Times.

A NEWSLETTER FOR YOU

Asean Business

Business insights centering on South-east Asia’s fast-growing economies.

ITL, a Ho Chi Minh City-headquartered firm, operates the Yen Vien international multimodal railway station in Hanoi.

But these benefits are not exactly cost-free.

Vietnam’s manufacturing and export industries still rely heavily on imported materials and goods from China, its largest trading partner.

Faster and more direct movement of competitive Chinese goods via cross-border express trains may thus expand Hanoi’s trade imbalance with Beijing, which already stood at a nearly US$50 billion surplus in China’s favour last year.

“Vietnam’s high-speed rail initiative with China is a double-edged sword. While it promises economic benefits and improved supply-chain efficiencies, it also risks exacerbating the trade deficit and increasing economic dependence on China,” said Dr George.

There is another area of doubt about the commercial viability of the new rail lines – the currently limited flow of goods between the two countries via rail. Goods that were transported this way accounted for under 0.1 per cent of the bilateral import-export turnover last year.

The ITL Corporation spokesman suggested that this may be rooted in the limitations of Vietnam’s existing rail system.

The country is still using its hundred-year-old rail system built in the days of French colonial rule; its gauge standards and train speeds are far behind those of China’s advanced rail network.

As a consequence of this, businesses have preferred to move their goods by road or sea.

In a report last December, a Vietnamese transport consultancy consortium indicated that the current and projected trading volumes that would use the rail link between China’s Kunming and Vietnam’s proposed rail nodes of Lao Cai, Hanoi, and Hai Phong are too thin to justify the early construction of additional rails or replacement ones.

The report further noted that the forecasted transport volume across the Vietnam-China border is highly variable, heavily dependent on diplomatic and economic trade relations between the two countries.

Renewed efforts from Vietnam

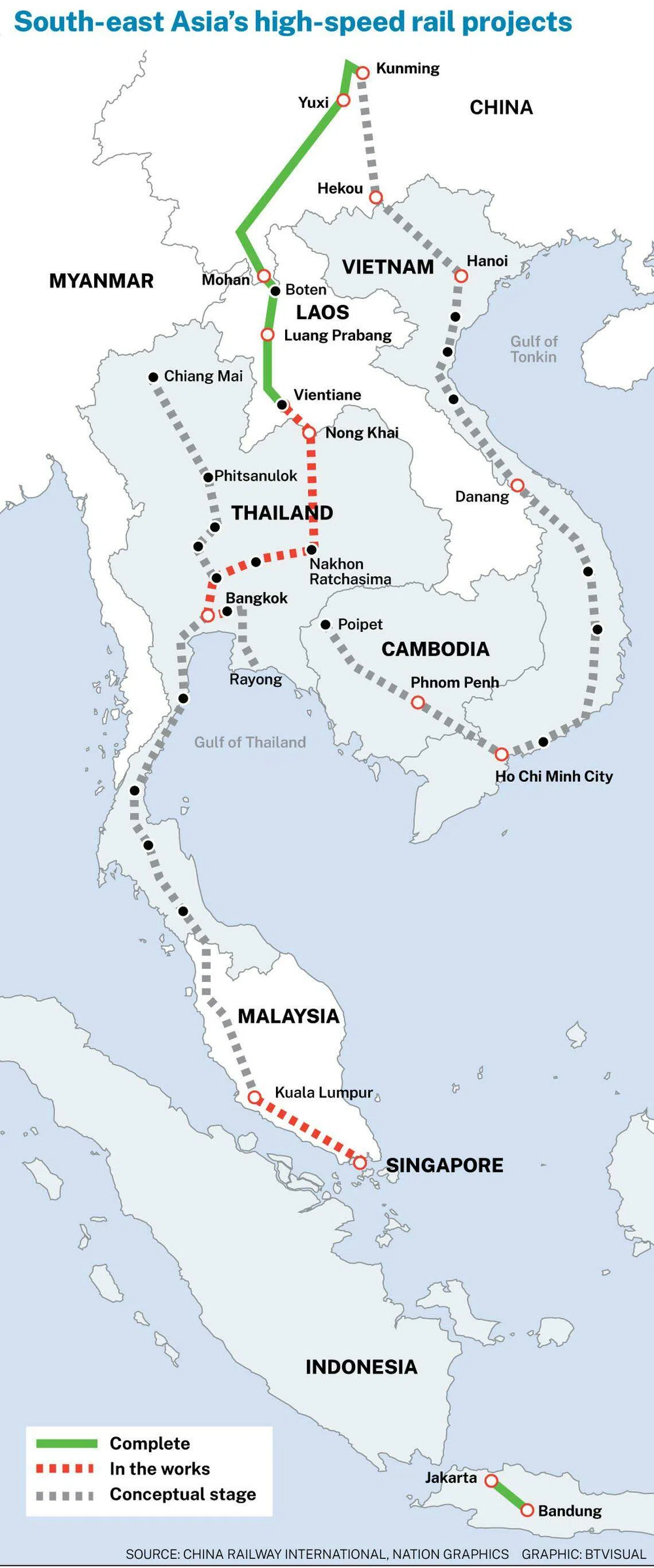

China now boasts the world’s largest high-speed railway network. Its bullet trains already cross the border into Laos, but have yet to cross into Vietnam.

Beijing has extensively funded rail routes in Laos, Thailand and Indonesia under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the region over the years. Vietnam, on the other hand, has been relatively cautious about taking part and receiving China’s BRI funding for infrastructure projects like railways, and so is lagging behind its neighbours.

The amount of funding Vietnam will mobilise for the two rail lines remains unclear, as does the number of contractors and amount of technology from China it will tap.

If the amount is significant, observers worry about potential Chinese debt burdens for the South-east Asian nation, and the risk of years-long delays associated with Chinese-built projects.

Of the two high-speed rail lines, the first is planned to run from Vietnam’s port cities of Hai Phong and Quang Ninh; it will pass through the capital Hanoi and run to Lao Cai province, which shares a border with China’s Yunnan province.

The other rail line is set to stretch from Hanoi to Lang Son province, adjacent to China’s Guangxi region, cutting through an area densely filled with global manufacturing plants.

These two sections will be connected to Vietnam’s US$70 billion North-South high-speed railway project – a 1,500 km route linking the capital Hanoi with the southern metropolis of Ho Chi Minh City, and which Vietnam aims to open by 2045.

This is also a part of the eastern route of the Kunming-Singapore railway, also referred to as a pan-Asian high-speed railway network connecting the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor envisioned by China’s BRI.

Reaping the fruit of strong ties

Vietnam’s high-speed railway plans are also getting a push from its mounting agricultural exports to China.

Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh earlier this year called for rail transport to be stepped up and modernised, in order to crank up shipments of agro-forestry-fishery products to China.

The agriculture industry was Vietnam’s biggest contributor to its trade surplus last year, accounting for 42.5 per cent. The sector’s exports surpassed US$53 billion in 2023, resulting in a 43.7 per cent year-on-year surge in trade surplus to US$12 billion.

This was partly led by warmer trade relations with China, Vietnam’s largest fruit buyer, which is now allowing for more Vietnamese produce to enter its huge market.

In July 2022, Bejing enabled bulk orders of Vietnamese durians under the official quota, which sent durian exports to China up tenfold last year. With US$2.2 billion in revenue mostly derived from China, durian became Vietnam’s key export fruit, accounting for almost 40 per cent of total fruit and vegetable exports in 2023.

Observers viewed this move as Beijing’s effort to strengthen ties with its South-east Asian neighbour amid the ongoing maritime disputes in the South China Sea and increasingly friendly relations between Vietnam and the US.